Writing when there’s nothing to see…

This text is the product of reflections and questions that accompanied me throughout the quarantine. It was written in March and April 2020.

No more outings, no more physical contact, no more shared moments other than within our own walls, no more heated debates except via choppy videos and restrained discourse. No more of anything “unnecessary,” no more galleries, museums, art centres, no more studio visits, no more exhibitions. Nothing left to discover, to love or hate, no more untidy feelings to be carried through the day and thought out later. Nothing more to see.

Like so many at the beginning of the quarantine, I, too, was bursting with resolutions that would make my confinement “productive,” especially the resolution to write, because now — I thought — I would have the time. Sure, but what would I write about with everything closed? An overview, then, a little more than a month later.

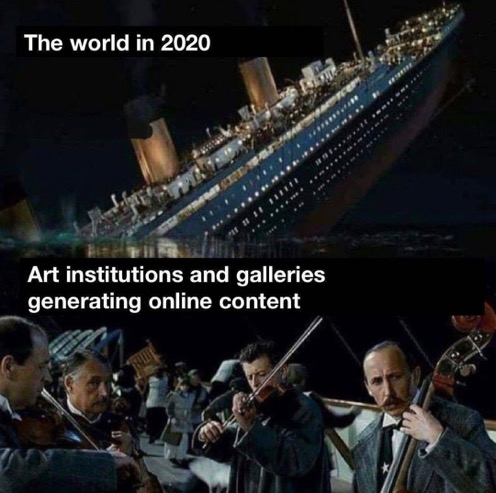

As soon as the confinement began, I quickly saw a tenfold increase in digital activity from actors in the art world. What at first appeared to be a necessary vital impulse, a dematerialized survival instinct, then left me pensive. What if, in seeing too many works, exhibitions, visual content of all kinds, we ended up no longer seeing anything at all?

We thus witnessed the emergence of another art world, intense in its virtuality. Like an organized struggle against paralysis, initiatives have multiplied, to try, in spite of it all, to continue to exist in the face of the abrupt cessation of everything. As the days go by, virtual exhibitions, videos, focus sessions and other takeovers are heaped one upon the other in our news feeds. Sometimes it’s enough to makes you nauseous. While I understand and share many of the concerns that animate the art world in a legitimate way, I wonder what this very active virtual world actually produces. Since exhibition spaces have been forced to close indefinitely, everyone has had to wonder about the possibility of remaining active and, above all, visible, at all costs. The digital thus seems to be the only — indeed, the last — possible refuge in response to the closure of spaces and the ban on receiving the public. For galleries, museums, art centres, artist-run spaces and others, it has become much more than a tool for internal work or communication. It is now the only space available for showing, exhibiting, making visible, and, if possible, making sales.

That month we thus attended the first international virtual contemporary art fair, with the dematerialized version of Art Basel Hong Kong and its preview viewing rooms equipped with early access codes for VIPs. A good number of exhibitions, barely underway when they were brusquely interrupted by mandated quarantine, continued online. Virtual auctions were held, such as the one organized by Piasa to benefit the Protect Your Caregiver collective. For others, it’s been an opportune moment to reassert their status. At just the right time, Hauser & Wirth launched ArtLab, a branch dedicated to projects that combine art and technology whose first initiative is a virtual reality exhibition modeling tool. In the article “What happens after the contactless art world?” published on the WCSCD website, Nikita Yingquian Cai reports that the private museum MWoods in Beijing has created a virtual gallery in the popular video game Animal Crossing (1).

Beyond these particularly notable demonstrations of strength, most structures, both large and small, are seeking to make maximum use of their social networks, animating them with photos of works, exhibitions, portraits of artists or shots taken in their studios, etc. Within this large batch of initiatives some are more remarkable than others, and these do not necessarily emanate from contemporary art’s most notable heavyweights. But they are all events that seem to say “we are still here, we are still strong”.

It resembles a kind of latent anxiety syndrome, a response to a new mantra: do everything you can to avoid disappearing — at the risk of saturating the visual and mental space of Viewer 2.0. At the risk, too, of provoking a form of overbidding within the system itself. Actors pit content against content, creating an almost-permanent presence, under penalty (the cruelty of algorithms) of being swallowed up and disappearing. And even virtually, injustice persists. Not everyone plays with the same weapons, not everyone has the material and human means to embark upon the creation of a virtual platform or a 3D visualization of an exhibition. So not everyone can afford to be innovative. And the smaller players find themselves at even greater risk of being crushed by this wave of digital ubiquity.

That the art world is concerned about the possibilities of its digitization appears to us a natural phenomenon, a logical continuation of the evolution of our present world. But we can regret the dominant use that is made of that digitization. Some seemed to have accepted that for a while it would not be possible to carry on with “business as usual,” to play at normality in an abnormal time. They have used digital technology to gently push a different perspective on their initiatives, the works themselves, or their exhibitions: to approach creation and its surrounding landscape differently, often through words rather than images, since the exhibitions are temporarily invisible (2). And we can only welcome these initiatives, which testify to a reflection on the possible uses of digital technology in the art world without seeking to replace the physical experience with the virtual.

Going to see an exhibition, looking at works, becoming aware of a given scenography, of the coherence — or its lack — of the works amongst themselves, of the circulation induced, is above all an experience. A sensitive, physical experience, apprehended by our eyes, our ears, our whole body. It is also an experience of space, and of our own body in the space produced by the exhibition.

“Social distancing” does little for a work of art. To see works is to encounter a whole in a given space-time, and in a given physical and mental state. It is the experience of an instant that can only come about through a physical encounter. A great deal of sensory data is needed, data that even the best virtual exhibition views cannot reproduce. The work whose reproduction we admire in photography is in truth no more than an avatar. And if visual information is essential to our contemporary societies, it is at best the trace of an experience — not the experience itself.

Art criticism too is first and foremost a matter of encounter: with the work, with the exhibition, with the space, with the artist. Writing then attempts to transcribe this sensory encounter into words. Paradoxically, it intends to translate that which inherently cannot be said. It is not a question of describing what we see, nor of analyzing it as the art historian does, but of sharing the personal experience of this encounter, be it good or bad. But in our times, when our networks are indeed saturated with visual content, what encounters can we still bear witness to? How can we write, and what on, when there is (no longer) anything to see?

By visually saturating the digital space, do we not run the risk not only of generating both frustration and weariness, but also of gradually and unwittingly stripping art of its mystery, of that which creates wonder — more necessary than ever in times of crisis? There is nothing normal about what we are experiencing at the moment: this cannot be repeated enough. Why, then, seek to maintain this absurd appearance of normality?

If there is nothing normal about the situation, then it should be no wonder that there is nothing to see. And if there’s nothing to see, there’s still plenty to think about.

April 2020

Footnotes :

(1) Nikita Yingqian Cai, « What happens after the contactless art world? », WCSCD, april 2020, online:

http://wcscd.com/index.php/wcscd-curatorial-inquiries/as-you-go-journal/what-happens-after-the-contactless-art-world/?fbclid=IwAR1sSxAbxNeIJIX0P-hym8Cv9v9B6fi9hu2K8gvWL1DabV6IV8MQuB4n1Fs

(2) Among comforting initiatives that come to mind: Backslash Gallery's “Petites histoires en vidéo,” the Sator Gallery’s “Vous avez une minute?”, devoted to short readings of texts on works or exhibitions, or Camille Bardin's podcast, “Présent-e,” where she speaks with artists about what exists upstream and downstream of creation.