Open a text space : Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster and Théo Casciani

What other artist than Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster could have become the character of a novel in this new literary year? In Rétine, playing with the artist’s public image and reported comments, Théo Casciani imagines her almost mute. Known to insiders by her initials, DGF has brought literary and cinematographic issues into the field of contemporary art. In her work, she develops fictions and plays multiple characters, from Fitzcarraldo to Marilyn Monroe, from books, films and life. Above all, she invents environments, spaces of passage and possibilities between worlds such as the Cosmodrome, created in 2000, between earth and space; or the Expodrome, created in 2008, which plays on the very possibility of an exhibition. With the Textodrome, designed in 2019 for the small room of the Centre Pompidou during the Festival Extra!, the artist wonders how to present a text.

The text appears as a material in Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster’s work since Textorama presented in 2009 as a “giant calligram”. Set on a long white wall, it evokes a landscape of quotes with three climates, tropical, desert and Atlantic. With the Textodrome, the artist offers a screen space for a set of texts of different natures: textofilms, textoslogans, textodreams, textosongs, textotextos… For her, the Textodrome is also “in a funny way […] a space to send text messages. What is rather poorly seen in cinema but[which] is increasingly being done[in] concerts or[in] other public performance spaces: the small screen coexists with a large screen where the text is displayed.” In concrete terms, these are sentences that scroll across a screen. They may have been invented for the occasion or taken from previous works or taken from what the artist hears on a daily basis. Some of them also come from literary works, including the novel Rétine by Théo Casciani: the circle is complete.

Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster often uses the printed book as a building and inspiring material, but it is only one of the possible forms of appearance or presence of the text in his works. Among her references, Godard’s credits and subtitles are alongside the complete works of Jenny Holzer, Barbara Kruger and Lawrence Weiner. It is not only the visual device that interests DGF with Textodrome, but also, as the suffix -drome indicates, the very space of the text. Dramatized by red and blue lighting, the projection room is adorned with disturbingly strange colours. Textodrome is a setting, a place of darkness where the reader’s imagination is swallowed up. As soon as he enters, the artist blurs the markers by superimposing the title of his work in blue neon on the name of the place. The room is anchored in a particular, ephemeral temporality, that of a festival where films follow readings, and readings follow encounters, as an echo of the artist’s multiple activity.

As a place of literary representation and textual space, the Textodrome emphasizes the importance of the role of the reader or spectator in the life of a work. “It is not surprising to stay 5 minutes and not feel anything,” Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster asserts, “reader and spectator are always active, otherwise nothing happens… the good readers also make the good books and the same for exhibitions. “In the same way that the visitor is invited to become a reader at DGF installation, the reader is invited to become a visitor at Théo Casciani. In Rétine, the author imagines an exhibition of the artist in the prefectoral art museum of Hyōgo in Kobe. The works, most of them fictional, are based on a knowledge of the artist’s approach and on the temporary suspension of disbelief specific to the novel; they allow an artist’s corpus to be enriched to better hypothesize her singularity. Thus, the screen room, traversed by a flow of images organized by an algorithm imagined by the author, proposes to experiment with a visual, spatial work through thought and text, which is the exact complement to DGF environments that act on the imagination based on visual and sensory stimulation.

“The work of art does not have to be made to have the status of a work of art,” Lawrence Weiner stated in 1968, laying the foundations of conceptual art. Since then, many artists/authors have been able to move from the literary field to the artistic field without worrying about labels. Having completed the master’s degree in creative writing at La Cambre, Théo Casciani does not seek to categorize his practice. Thus, he creates installations, frames and composes stories, fictions. Many readers have seen Rétine as a narrative based on the codes of the Nouveau Roman and a writing requirement similar to that of Jean-Philippe Toussaint. The narrator crosses a world that he transcribes as precisely as possible in a permanent ekphrasis exercise. Writing is like an attempt at exhaustion, a search for a hold on the world that leads the reader to open his eyes. The reader’s responsibility is not simply to imagine what is written and which does not necessarily exist elsewhere, but to establish links with the reality around him. Rétine is a novel of persistence where the modalities of the image are constantly questioned, whether they are extracted from a film or TV news, taken from the Internet or from a Skype conversation.

The book by Théo Casciani raises the question of the screen and the filters by which we apprehend reality. The book’s inaugural scene describes the flight of an airplane that skims two twin towers and merges for a moment with the high-profile images of September 11, 2001. Patrick Bouvet with Direct was interested in the astonishing power of these images and their live relays on all the channels in the world, but in 2019, this evocation draws another observation on the way in which information and especially false information circulate. The image can always be misinterpreted, turn out to be a montage or false pretence and it is more important than ever for readers, spectators, to be vigilant. The role of the narrator in Rétine is thus to sort and organize the images for the DGF artist. A heavy responsibility, an ant’s work that ends up escaping him and revealing at times an unconscious that is also that of an era… If we draw a parallel with the flow of texts, images and sounds of the Textodrome we see in the same way stories recomposed from various fragments. Unresolved, unwritten but implied stories: a narrative gift.

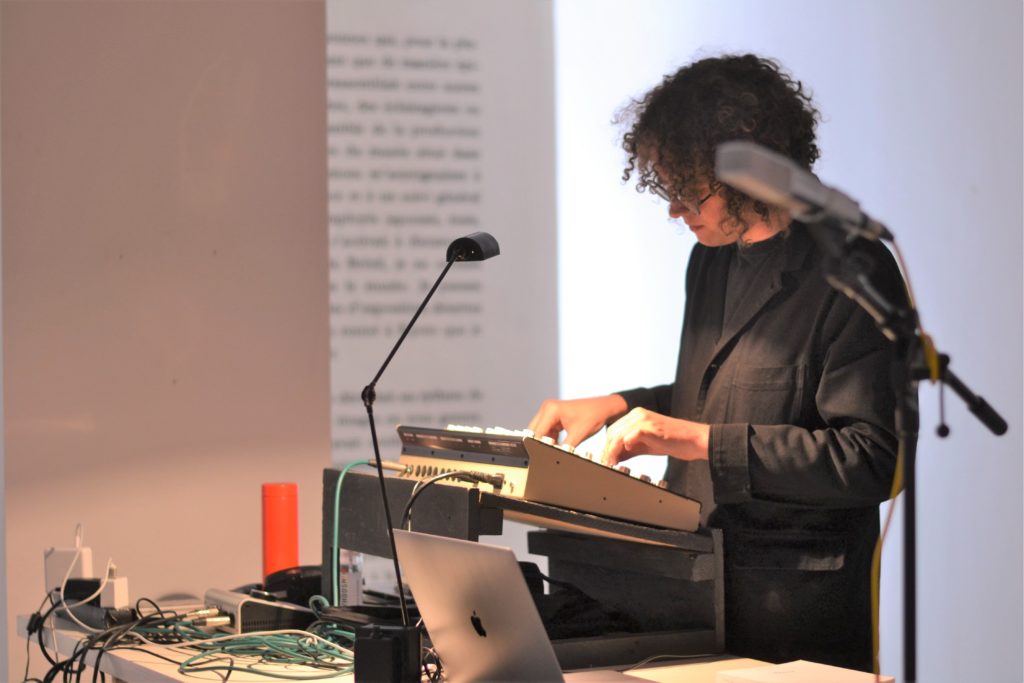

“Textodrome” is also a term for word processing software. We could see this proposal as a creative space where ideas are sketched out and affirmed, where images pass through and forms are tried out. Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster pushes characters and throws narrative frames without ever choosing, as if she were reconfiguring her own practice and taking the spectator as a witness. She opens a new door on her work just like Théo Casciani who makes her novel the very space of play with reality, a performative space. He printed some pages of his story on leashes that he reconfigured in different contexts (the Centre Wallonie Bruxelles in Paris in September for example) to literally get the reader into the text. In this space, which is more fixed than the Textodrome, he invites different personalities (choreographers, musicians, artists or actors) to take over the text and testify to their visions. The constraint of a common book makes it possible to enhance the sensitivity of readers, to enrich and push the limit of a book, to direct the gaze on the challenge of a literary space of representation. The two proposals of Rétine and Textodrome deconstruct the space of the text to facilitate its appropriation and call for a demanding design of the reader/viewer. They show that art and literature have never ceased to expand their borders only to meet and ask the question of narrative.