KAREL APPEL, L’ART EST UNE FÊTE !

Inaugurated a few days before the closing of the Bernard Buffet, the exhibition Karel Appel L’art est une fête ! presented at the Musée d’art moderne de la ville de Paris until August 20, highlights the desire to re-read monographs by major 20th century artists. Karel Appel was born in 1921 in Amsterdam and died in 2006 in Paris. The artistic label is formalized, the CoBrA group is traced in the background. However, this vision is far too simplistic, and this is the original point of the exhibition, its journey through the artist’s entire career. It was made possible by an exceptional donation from the Karel Appel Foundation in Amsterdam of seventeen paintings and four sculptures, complementing the works previously in the museum’s collections.

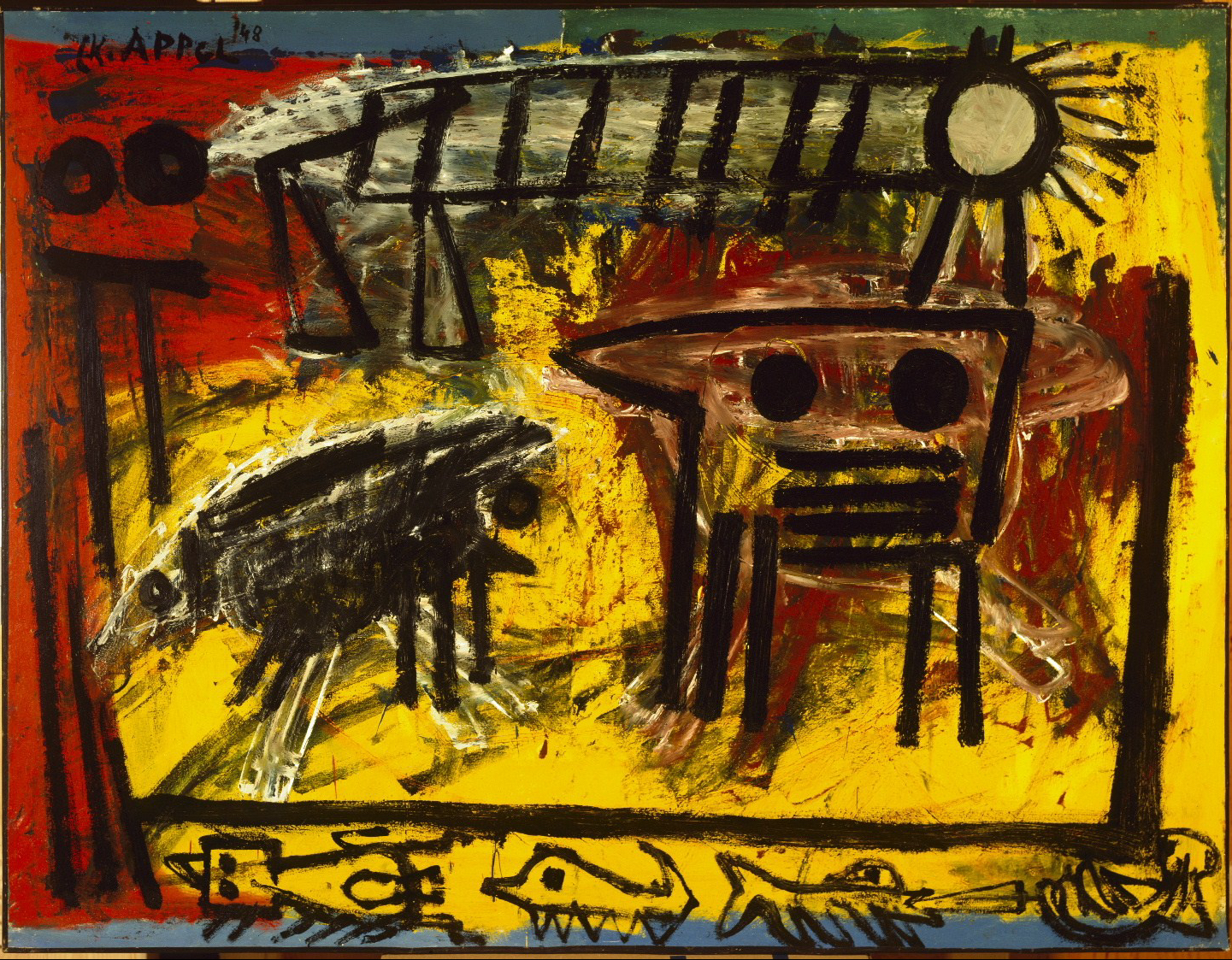

Invasive is one of the first words that comes to mind when facing a work by Karel Appel. Whether for sculptures or paintings, the deployed material catches up with the environment and freezes on our retina. Nearly sixty works are exhibited on a clear and limited route, giving an intimate character to the exhibition space. Four periods are divided into almost complete decades. However, the works guide us in Karel Appel’s artistic evolution and clearly exacerbate the evolution of his creative spirit. A reminder of his period with the CoBrA group is necessary to understand the founding aspirations and inspirations of his art. Created on November 8, 1948 in Paris – dissolved three years later – by Karel Appel, Asger John, Constant, Corneille and Joseph Noiret, the name CoBrA is the contraction of the artists’ original capitals: Copenhagen, Brussels and Amsterdam. It is a gathering of artists, rejecting the almost “academic” formality that abstract art had reached according to them. They then put into practice an experimental art turned towards a more objective imagination, oscillating between two main figurations, the animal world and that of childhood. The works presented in this first section are in all formats. A multitude of characters of primitive and vividly coloured appearance are painted on a black background – almost recurrent – following a line with ill-defined contours that seems “simplistic” and devoid of any technique, as in the works Monde animal (1948) and Petit Hip Hip Hip Hourra (1949). This return to childhood can be perceived as a desire for total abandonment, a loss of control in order to find creative reflexes. In the sculpture, Karel Appel adapts the characteristics of his painting, the arrangements of pieces of wood nailed to the surface become totems, on which he paints figurines with exorbitant and almost threatening eyes (Enfants quémandant, 1948). Not wishing to assimilate himself to the political demands of the CoBrA group since the late 1940s, Karel Appel distinguished himself in his practice and followed a personal path in a constant need for pictorial renewal. The 1950s were the beginning of a cult of the vivacity of the material.

The reading of his work is also done by bringing together his two favourite media, painting and sculpture, to which is added ceramics. The formats are getting bigger and the scratch of the canvas is made by a pure material with intense colors. The exacerbated materiality shifts our focus to the edge of the painting. This oblique vision opens onto an organic, living and almost palpable field, where the surface of the canvas becomes a heap of steep reliefs. The motif accumulates on a neutral background, it becomes a suspended formless pile, a formal ring. Indeed, the artist begins a painting with a tube, he now affixes the material as it is, without working on it (Danseurs du désert, 1954). The film La Réalité de Karel Appel, shot in 1961 by Jan Vrijman, presented at the centre of the exhibition, sums up the process used by the artist. The staging shows a face-to-face encounter with the canvas, where the artist becomes a craftsman facing a raw material. The animosity of the act makes his painting trivial, the canvas vibrates under the frenetic stab wounds projected by the artist with both hands. This six-minute sequence traces the development of a huge painting, Archaic Life, hanging in the rest of the exhibition. The result is consequent, the stratification of the pictorial layers acts on the canvas, which, deformed under the weight of the material, synthesizes all the violence and dynamism of Karel Appel. He himself claimed it: “I do not work for art, nor for painting. But because I want to. It’s fighting with the material that interests me more than art. Sculpture in the 1960s exalted the artist’s entire fantasy, as in the work L’Homme hibou n°1 (1960), where an olive tree stump became his experimental matrix. The last part of his work shows a softened gesture. The human figure remains its absolute reference and matter is no longer a formless cluster, it spreads more widely over the surface. His painting becomes somewhat dramatic, where the colour, far from its original acuity, borders on the bitterness of the condition of the man in the making (Les Décapités, 1982). From the 1980s onwards, his creative spontaneity would continue in his sculptural practice, far from the primitivism of his early days. It gives way to the arrangement of figures taken in the world of entertainment and carnival (La Chute du cheval dans l’espace silencieux, 2000).

This monographic exhibition provides an insight into the history of 20th century art and its constituent artistic movements. In the 1940s, Paris was still the nerve centre of art, despite the repercussions of a war that led to the exile of artists – mostly surrealists – and the birth of abstract expressionism, thus making New York the catalyst for new aspirations. This artistic shift crystallizes in Karel Appel’s artistic production, and allows a transversal and retrospective view of this period. It was in 1950 that Karel Appel moved to Paris, a city for which he would always display an unfailing bond: “If Amsterdam is the city of my youth, Paris is the city of my evolution. What I learned there takes precedence over everything else. Michel Tapié, theorist of “informal art”, will be the central pivot in the Parisian period of the artist and the impresario of his encounters and his future. The art critic, defender of this new gestural art that he called “other art”, will see in the person of Karel Appel one of his most keen investigators. The painter paid tribute to him in a 1956 work Portrait of Michel Tapié by Céleyran, which, despite the abstraction, did not blur the subject’s recognition. In this decade of the 1960s and 1970s, the artist concentrated on the same themes. Karel Appel’s artistic journey is punctuated by artistic confrontations, which after those in Paris, will be concomitant with the New York modernist adventure. In 1957, he inaugurated the many stays he later made in the city. The large formats used by Appel are echoed in those used since the late 1940s by Jackson Pollock, a leading figure in American abstract expressionism, defined as “action painting” by Harold Rosenberg in 1952. Gestuality and spontaneity are therefore the variables around which this painting of the order of performance is delimited. Jan Vrijman’s film is reminiscent of Hans Namuth’s, which are essential documents for understanding the material processes used in Pollock’s work. However, unlike its detractors, Karel Appel will never deny the figuration and will never question the verticality of its support. Pollock indeed painted on the floor. Later, it was in the spirit of pop art that the artist in the 1960s confronted painting and the object on the same level, with a portrait in sparkling colours on display.

The “Ode to Joy” granted to the material by Karel Appel is singular and retains all its brilliance. His career spanning the second half of the 20th century, shows the upheavals that have disrupted artistic practice. However, the singularity of her work is not based on an artistic label, she displays a constant desire to create. Art is indeed “a celebration” as shown by what can be considered as his pictorial testament, his work Feestje? from 2006, which in Dutch means “small celebration”. It is therefore a pleasure to walk through it and celebrate it.

Diane Der Markarian

- Extrait du film de Jan Vrijman, La réalité de Karel Appel, 1961, Photo : Ed van der Elsken / Nederlands Fotomuseum © Ed van der Elsken / Nderlands Fotomuseum / Courtesy Annet Gelink Gallery

- Karel Appel, Nu blessé, 1959, huile sur toile, 183 x 243 cm, Musée d’Art moderne de la Ville de Paris © Karel Appel Foundation / ADAGP, Paris 2017

- Karel Appel, Petit Hip Hip Hourra, 1949, huile sur bois, 74 x 100,5 cm, Musée d’Art moderne de la Ville de Paris © Karel Appel Foundation / ADAGP, Paris 2017

- Karel Appel, La Chute du cheval dans l’espace silencieux, 2000, objets trouvés et huile sur bois, 144,8 x 243,8 x 162,6 cm, Musée d’Art moderne de la Ville de Paris © Karel Appel Foundation / ADAGP, Paris 2017

Featured image : Karel Appel, Les Décapités (détail), 1982, huile sur toile, 193 x 672 cm, Musée d’art moderne de la ville de Paris © Karel Appel Foundation / ADAGP, Paris 2017.