About a beauty experience

It is quite unusual to read critics express themselves on beauty. We can understand that, there are many reasons. Because it is not a value immediately sought in the world of contemporary art, where the “wish to say” prevails over the “show” (1), because the artistic process has taken precedence over the final form, this reinforced by decades of curating and their imperative to talk about the world – the exhibition is both a discursive and spectacular tool, and when it concerns experience, playfulness or “interaction” are valued. Above all, I think, because the apprehension of beauty is not so much a matter of evaluation, the correspondence between the visual artists’ proposals and the criteria that would distinguish the simple proposals with “art”, therefore a social phenomenon, as of an affect, a singular and intimate attachment, which necessarily is a nakedness, a way of revealing oneself in its fragility, that of its tastes, its subjectivity. A way of revealing the “feeling self” rather than the “stating self”, the latter already depicting an identity constructed as a political fiction. Basically, this is a bit like the observation made by Susan Sontag (2) when she regrets our relationship to the work, the exclusionary search for content and meaning to the detriment of the senses, and the fact that « interpretation [takes] the sensory experience of the work of art for granted, and proceeds from there. » Before continuing: « This cannot be taken for granted, now » and to urge his contemporaries to change their approach, in a formula that has become famous: « Instead of a hermeneutic, we need an erotic art. » In short, a relationship to the artistic experience (and its commentary) that she felt should have been removed (in 1966) from the only cold and objective interpretation, in order to regain its spiritual and sensual value.

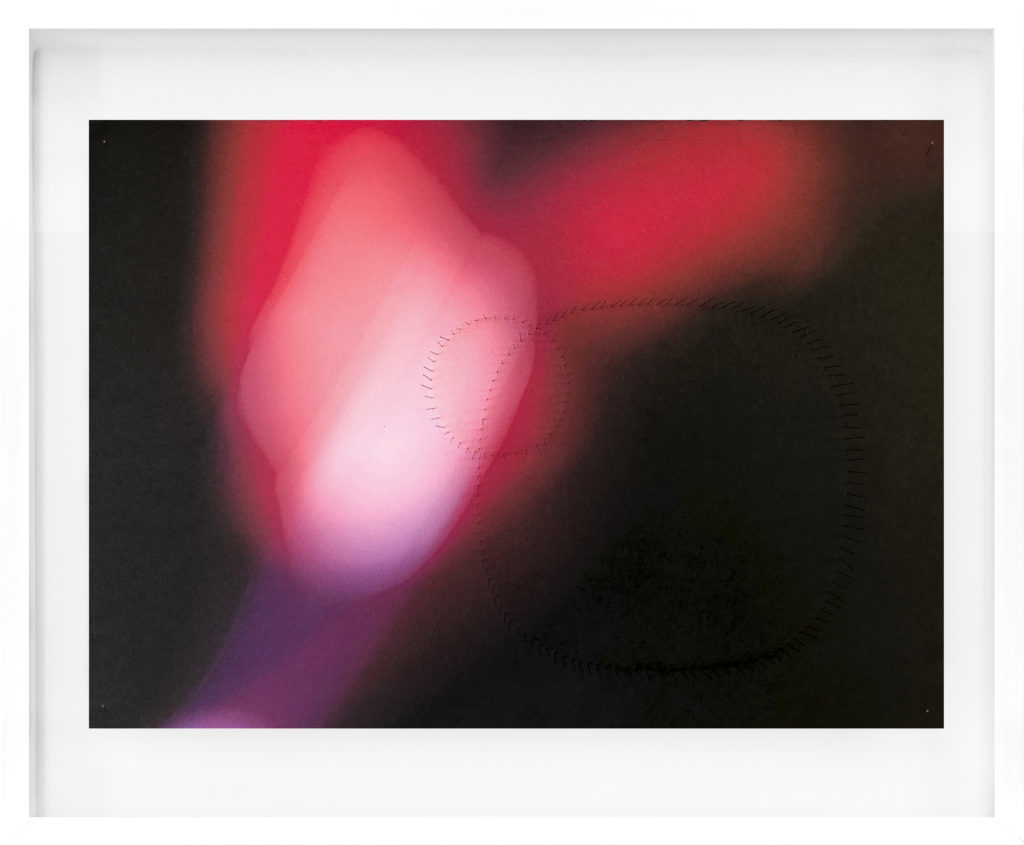

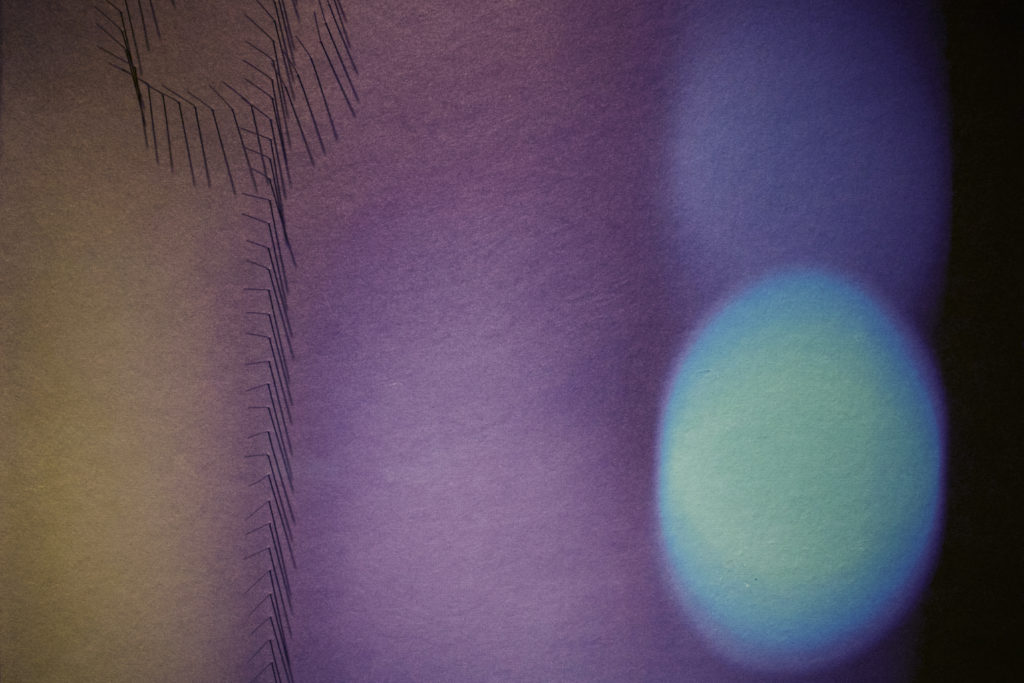

It was an experience I had recently experienced at the Da-End Gallery that gave me the desire (urgency?) to write this text. This experience has been felt several times since, perhaps guided by a very romantic nostalgia, I have come back to live it again, or rather to provoke it again, we never live again these moments of beauty. Da-End’s exhibition on Satoshi Saïkusa includes four small pieces in the space at the back of the gallery. At first glance, they play the indistinction of the medium, we don’t really know what these large, intense, coloured surfaces are made of, until we notice that they are prints on Japanese paper – kozo, to be exact. Abstract photography, almost, since some details end up betraying themselves, so that we perceive that the sources of these images are the lights of the city. Here, the lights of a car seem to stand out in pure form, here a sign. Discrepancies. These pictures have given up their signified to signify themselves. Satoshi Saïkusa has not kept a significant image of reality, the common lot of photography, he captured its light – in a pure gesture of a photographer one could say, “the writing that proceeds from light”. The tyranny of Roland Barthes’ “it was” (3) ebbed back, we don’t know what was photographed. It is, simply. These pieces have the sovereignty of certain images without referent which, expressing nothing, exist for themselves with renewed vigour. The aggressive colours of the city, the neon lights, the lighthouses, the signs, all those raw lights that pierce the night rather than illuminate it, were collected and transformed, through the mediation of the apparatus and then the printing, into delicate colours with fading contrasts. These colours, I have not yet named them because I believe that our words lack the feeling that their gradation gives me, they are not absolutes, but nuances. The Greeks, in the classical period of their time, saw in ξανθός (Xanthos) a plural colour ranging from yellow to red, the word referring both to the animal’s fawn and to the blond curls of homeric heroes or to the glow of bronze forges. This term is more appropriate for the first two pieces, such as κύανος (kúanos), from which the term cyan derives, but which differs from it, seems to me to better describe a third one. Related to καίω, kaíô (“to burn”), it refers to a dark glow, ranging from the deep blue of steel to the glow of lapis lazuli. And even then, these vibrant colours would be nothing, bland, without the entomological pins that came to prick them and draw simple geometric shapes on their surface. Sober forms, but particularly touching by their imperfection, . Such circle does not have the arrogance of the perfect orb as long as the indolence of the subtly collapsed circular form, such line takes some liberties with straightness. A simple device, the colourful beaches pricked with needles, which is revealed in the particular space of the Da-End gallery, poured into the penumbra of traditional Japanese interiors, those evoked by the aesthete Junichiro Tanizaki (4), and which takes the decision to reveal the works through a soft and radiant light, rather than a raw exhibition in a homogeneous light, in addition in neon. In such a place, the shadows cast by the pins would be lost, faded, and the beauty of the pieces with it. Because beyond the harmony of colours and simple but imperfect shapes, what touched me those few evenings was the way the place and its exhibitions are in harmony – without neglecting the heady and floating smell of the flowers nearby. The shadows of the pins and the coloured reflections on their stems bring brightness and complexity to what was measured and simple. The ethnologist Franz Boas (5) tirelessly links art to the idea of rhythm, which, together with symmetry and the accentuation of forms, represent for him the three universal aspects of the artistic phenomenon. Rhythm is the variation, of touch, tone, material and manner. It is their inclusion in this space that gives rhythm to the works, so that they seem to belong to the place in which they are exhibited, they seem immutable where they generally succeed one another. It is this intensity of being and presence, despite the simplicity and softness of the pieces, that deeply touched me. Perhaps, in this case, my “sorrowful spirit will only regret the white frames, too thick, almost brutal, for works whose beauty lies in a projected shadow.

The beauty experience is solitary, but it is not individual. Concerning this series, during my visits to the gallery, I perceived the interest and particular curiosity that it inspired in those who saw it – I will be excused for the lack of objectivity of this investigation. In short, we experience it alone, but we are not alone in doing it. So, we can express ourselves about it, which criticism avoids. I cannot help but think that this is a pity, in various ways, because a central aspect of the aesthetic experience is ignored, as well as many artists whose work passes outside the radar, to the benefit of others, sometimes with snoring messages and hollow ideas. Perhaps, a cause for this would be to be found in the fear of the lack of subject. The fear of not saying anything about beauty, whether it seems firefighter, romantic or vain… These lines were written with great sincerity, and perhaps if I read them again soon, I will indeed find them hollow and bland. A judgment that will not concern the works of Satoshi Saikusa, but my speech. But that, in any case, does not distinguish interpretative writing from sensual writing, if they can be described as such. We never write completely about an artist, as much as about the evolution of our gaze or our thinking through him.

(1) Based on a distinction by Marie-José Mondzain in Homo spectator, 2007.

(2) Sontag Susan, “Against Interpretation (1966)”, in Anchor, 1990.

(3) Barthes Roland ” The clear room. Note on the photograph. “, Cahiers du cinéma, Gallimard/Seuil, 1980.

(4) Tanizaki Junʼichirō, Praise of the Shadow, Naïve, 2014.

(5) Boas Franz, Primitive art., vol. 8, Courier Corporation, 1955.

Until 21 December, 2019

Satoshi Saïkusa

Galerie Da-End

17 Rue Guénégaud, 75006 Paris