Cy Twombly – Centre Pompidou

“Just as the role of the poet since the famous letter of the seer consists in writing under the dictation of what is thought, what is articulated in him, the role of the painter is to identify and project what is seen in him”

Max Ersnt [1]

Until April 24, the Centre Pompidou can pride itself on offering its visitors an almost complete retrospective of the immensity of the work of Cy Twombly, an American artist with a heterogeneous and unclassifiable production.

In contrast to the artistic evolution of his time, Cy Twombly’s works deliver a universe that oscillates between myth and imaginary rereading of literature. The exhibition groups his works by theme and

is structured around three major pictorial cycles: Commodus (1963), Fifty Days at Iliam (1978), Connotation of Sesostris (2000). This easy gathering legitimizes the bias of a chronological journey, divided into decades, guiding the viewer through Cy Twombly’s constant artistic evolution. However, at first sight his art remains difficult to understand. The spectator’s eye becomes the visual cursor of the reading of his paintings, adjusting the necessary distance to apprehend his art. The gaze is carried out in two stages. A remote vision rooted in the diversity of the formats used by the artist, then a detailed one, in the specificity of his work. This is the case with the works presented in the first room, (Academy, 1955), which retrace the process of elaboration of Cy Twombly’s work during the 1950s, marked by the different journeys he undertook. Gratified by the criticism of making an almost essentially graphic art – always denied by the artist – in a typographical fatherhood that brings him closer to artists like Jean-Michel Basquiat, Twombly’s production is to be seen in multiple dimensions, at once linguistic, graphic and pictorial. The non-reporting of his writings projected on the medium leads us astray in the perception of his works. They seem to be an intimate jet of his intellect completed by the tremor of the writing they show. As the exhibition progresses, the painting gradually abandons the flatness of the canvas background. The thick construction makes it a heap of shapes and colours that detach themselves from the background of the work, which in turn becomes the terrain for the artist’s psychic divagations. We are faced with an almost carnal relationship between the artist and the canvas visible in his work School of Athens (1961). It should be noted that the sexual aspect is major in its production, the phallic forms being recurrent. Twombly plays with matter and its own evolution over time. His works are also a mix of techniques, lead pencil drawing is added to painting – industrial in its early stages and then oil – blurring the boundaries of these two materials subject to a so-called “traditional” art. The painting evolves through Twombly’s gesture. Not being able to be qualified as figurative, nor as abstract, it becomes the support of the artist’s duality with his own art. Cy Twombly expresses it himself: “I have more of an experience than a painting.

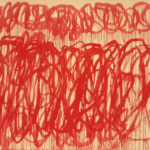

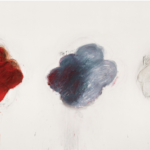

This material is a key to the artist’s impressive culture. She brings to life the themes addressed in her works. It also helps to establish its aesthetic, directly recognizable, and highlights an art promoted as “exceptional”. An aesthete of his time, the artist’s paintings represent the mirror of his erudition. It is in Mediterranean history that Twombly draws its aspirations from the heart of its founding myths and the tutelary authors of ancient literature (but not only). He lived a large part of his life in Italy, where near Rome he set up his studio in a house bought in 1975. This literal story becomes pictorial through its gesturality. The figures of ancient deities such as Mars, Venus or Apollo flood his paintings, he schematizes them in writing and shapes them in colour (Mars and the Artist, 1975). Twombly gave a primordial place to Homer’s stories and in particular to L’Iliade. The works of the Fifty Days at Iliam (1978) series are striking for their monumentality and the vehemence of their composition, the room dedicated to them immerses us in the story. The blatant red used by the artist fixes the violence of the Trojan War, the historical axis of the Homeric epic. The stain becomes a characteristic, as does the colour. His art evolves, the layout is amplified. From the 2000s onwards, the canvas was completely treated, the location of the composition was no longer selective. It becomes a bloody fresco whose shape is given by the bright colour used by the artist. And it is notably through the figure of the divinity of Bacchus wine, to which Twombly devoted a series from 2005, that its creation attests to a perpetual renewal. Not addressed in this article, the presentation of the artist’s sculptures remains a strong point of the exhibition. Built from the archaic arrangement of scraps, they shed light on the plurality of artistic media used by Twombly. Corroborating these, the photographs processed in series (five to six takes), freeze the object like a sensitive and pictorial poetry.

This retrospective dedicated to Cy Twombly is indeed a tribute to the scope of his work. With its many facets, it guides us to the heart of a medium that was almost forgotten during the second half of the 20th century and which once again acquires all its dignity through the prism of its works. Through the question of the philosopher Roland Barthes – who wrote on Twombly – “what is going on there? “, we must detect a direct entry into the artist’s sensitivity.

Diane Der Markarian

[1] G. Charbonnier, Le Monologue du peintre, Paris, 1959.

- Cy Twombly, Fifty Days at Iliam : The Fire that Consumes All Before It, Partie V, 1978, huile, crayon à l’huile, mine de plomb sur toile, 300 x 192 cm, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphie, gift (by exchange) of Samuel S. White 3rd and Vera White, 1989-90-5, Courtesy Centre Pompidou

- Cy Twombly, Coronation of Sesostris, Partie V, 2000, acrylique, crayon à la cire, mine de plomb sur toile, 206 x 156,5 cm, Courtesy Centre Pompidou

- Cy Twombly, School of Athens, 1961, huile, peinture industrielle, crayon de couleur et mine de plomb sur toile, 190,3 x 200,5 cm, collection particulière, Courtesy Centre Pompidou

- Cy Twombly, Sans titre (Bacchus), 2005, acrylique sur toile, 317,5 x 417,8 cm, Udo and Anette Brandhorst Collection, Courtesy Centre Pompidou

- Cy Twombly, Fifty Days at Iliam : Shades of Achilles, Patroclus and Hector, Partie VI, 1978, huile, crayon à l’huile, mine de plomb sur toile, 299,7 x 491,5 cm, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphie, gift (by exchange) of Samuel S. White 3rd and Vera White, 1989-90-6

- Cy Twombly, Mars and the Artist, 1975, peinture à l’huile, pastel gras, mine de plomb et collage sur papier, 142 x 128 cm, collection particulière, Courtesy Centre Pompidou

Featured image : Cy Twombly, Blooming, 2001-2008, acrylique, crayon à la cire sur 10 panneaux de bois, 250 x 500 cm, collection particulière, Courtesy Centre Pompidou, Paris.