Chalisée Naamani, « Nude selfies till I die* »

*May 16, 2016, Kim Kardashian’s speech receiving an award at the 20th Annual Webby Awards.

« 2020, je mets le Pape et Nabilla sur l’même tableau

Pas d’photo du corps d’Oussama, les G.I. l’ont jeté à l’eau »

Booba, 5G, 2020.

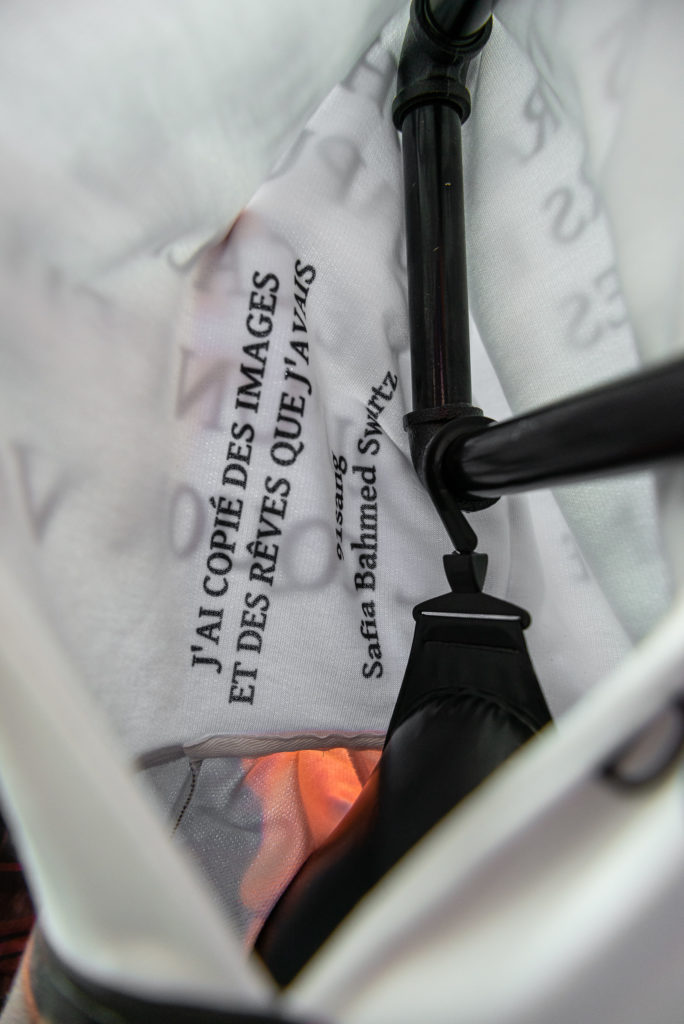

On @chaliseenaamani Instagram feed scroll flowers and bouquets, stars and constellations, rugs and quotes, polemics and calls for nominations, squares of glittery, low-cut, transparent or laser-cut clothing, photos from the end of the world and pieces of printed fabric, sewn, torn, wholesale or retail, high fashion or DIY, snippets of smiles or duckfaces, body parts from all sources – instagrammers, journalists, victims of police violence, supermodels, friends, followers – and of all shapes: damaged, assumed, bodybuilt, hidden, censored, exhibited, blurred, pimped, pixelated, retouched, redone… The posts and stories reveal, as she scrolls, horoscopes or news, be them artistic or political, in “public” or “close friends only” mode, @kimkardashian or @rayanemcirdi‘s latest party, @rokhayadiallo or @assa.traore_‘s latest interview, the last painting of @safiabahmedschwartz or the ultimate collection of @marineserre_official, the mantra of the day of @nadinejane_astrology or the next exhibition of the gallery @ciaccialeviparis (Spoiler Alert: it is dedicated to Chalisée Naamani and it opens soon…).

Chalisée Naamani’s Instagram feed is a diary, a notebook of inspirations and a means of expression. On her profile, she rarely shows her face. She hides it behind flowers or those of her friends, memories of her travels, Persian symbols and patterns, #OutfitsOfTheDay and, since graduating from the Beaux-Arts de Paris, photos of her graduation, her work and her latest pieces. Instagram, from intimate and encoded journal to public showcase and portfolio…

Shy, Chalisée Naamani? Her silver vinyl shoes or her pink cowboy boots, her leopard leather suit or the tight, liquid shark dress she made for herself to receive the jury’s congratulations for her fifth-year diploma at the Beaux-Arts de Paris, seem to say the opposite. “I dress to impress myself” once tweeted Kanye West. Who does Chalisée Naamani want to impress?

When I went to see her senior graduation, I was sure it was me. Flashy, blingy, lavish, a reference to the Renaissance here, the latest Comité Adama protest there – there’s something for everyone, gigantic flowers, in real and figurative bouquets, others woven into the thread of large drapes she’d spread across the floor and walls. It’s a good thing the Covid forbade celebratory buffets; it would have been gargantuan, for sure. Images were dripping everywhere in the school’s “galerie droite”, as if a thousand and one smartphones had come to disgorge too much accumulated data without having had time to digest it. Chalisée Naamani masters the art of pretending to do too much. I wander through her bazaar of images as if in a suddenly embodied Instagram feed. I step on eyes that look at me when I looked at them first and 211mio followers (that’s Kim K’s follower count) looked at them before me. I take pictures, everything is so beautiful, so perfect, so Instagrammable, cleverly put together. A priest’s chasuble made of reflective fluorescent yellow material on which an image of Piero della Francesca’s Madonna of Mercy (1462) has been printed dresses a hanger hanging on a coat hook, itself taken out of the button of a denim jacket, whose image is reproduced in gigantic and marouflaged on the wall – the first part of a wallpaper polyptych that lines the entire cyma. The second panel revolves around a clothing rack from which the clothes for a fitting are drawn; above it, a precious hybrid soccer jersey is framed under glass, accompanied by its scarf, to complete the panoply. It is custom made, both PSG and OM supporter – there is something for everyone, but this is a bit blasphemous, isn’t it? On the floor, Chalisée Naamani has left silk squares hanging quietly on the brass rings in which they are slipped when you buy them at Hermès… No flowers this time for the prints; the artist has made them from souvenir images of the foot of the Eiffel Tower: the mini and key-ring versions that those she calls “image sellers” sell to tourists who come and go, like them, from the four corners of the world, and that they carry around, like silk squares, at the end of large metal rings.

It’s a mess, everything is overflowing, everywhere. Couldn’t she choose? I heard that there are more than 35,000 photos, screenshots and images saved in her iPhone library… Perhaps her horror of emptiness comes from the anxieties of creative people, perhaps it is a consequence of the effervescence that lays in the act of scrolling, or of the Persian rugs that adorn the walls and floors of the apartment in which she grew up. I saw two things in particular in the overabundance of images in Chalisée Naamani’s pieces. On the one hand, an attempt to capture water with both hands. Capturing a physically inexhaustible flow, impossible to suspend, even for a moment. The story lasts thirty seconds, I react to it in DM with flames or heart-eyes, and in twenty-four hours it will only exist anymore in the archives of whoever will have recorded it. Chalisée Naamani chooses to capture the stories of her friends so that they are not forgotten. She makes cushions out of them, which she places on the floor so that we can sit comfortably in her exhibition. This is the second thing that struck me about Chalisée Naamani’s overabundance: a rare hospitality. To the fear of missing out, of not receiving properly, of forgetting something or someone, the artist responds with an excess of generosity, of delicate and refined food for the eyes and the mind.

On closer inspection, I have made this bazaar my own, I feel good, welcomed, expected. She who wanted to resemble the “codes” of contemporary art, purified, aseptic, “conceptual”, clean, smooth, white; she who was afraid to make clothes at the Beaux-Arts, and afraid to make paintings in a fashion school; she who was afraid to be noticed, to be assigned to such and such a community, to be told what to do, what to read, what to look at… She has managed to capture the “mainstream” codes (this word will make her shudder) and to sew her own. Penelope, while waiting for the return of Ulysses, weaves Time to postpone the date when she must marry another. During the day, she plays the game of suitors who believe they can abuse her; at night, she undoes, unweaves and imposes her own rhythm, writes her own story. Chalisée pretends not to understand anything, exposes the most followed sisters of the story next to the most invisible men. It is not necessary to wait for the night, however, to find the common thread between the two: from the Quechua tent, which she has set up in the middle of the right gallery, she has made the small house-bag of clothes that she had seen in her dream. In “L’habit(acle),” as she named it, and which you only get to after passing the silk and Eiffel tower squares mentioned earlier, it’s a very special photo of Kim and Kourtney that she put on the floor. The two Instagram superstars visiting Paris made a typical stop at the foot of the great tower, of which they buy miniature versions for their children. The photo with thousands of likes was printed in postcard size and is only visible through the wire mesh that the artist covered the plastic windows of the little tent. What’s left in the hands that tried to contain the Insta-spring water? Little pebbles polished by time and history, by the cultures and identities that have attached themselves to them and erected them into symbols. Likes and reposts, recorded publications and screens, little pebbles on the way to becoming miniature and digital monuments, insidious reflections of the identity symbols of the world wide web community. In 2020, Chalisée Naamani puts yellow vests and soccer jerseys, slogans and poems, the Eiffel Tower and the Arc de Triomphe, Hermès and Quechua, Traore and Kardashian on the same board.

On the carpet that welcomes people invited to enter her apartment is inscribed a Persian proverb: “Walk on my eyes.” The foot steps forward to crush the flowers and patterns of wool, gold or silk threads; it crushes and, in doing so, tightens the 10k (or 10mio, it all depends on the size of the rug) of knots that make it up, like pixels an image. To crush it is to link it, it is to “walk on eyes” that have seen the beauty of the world and give it back generously, it is to awaken it as one awakens the dead in cemeteries in Iran by walking on their graves. When she did it the first time, Chalisée Naamani thought she was profaning; but she is no longer afraid and only expects one thing now: that we walk on her eyes in turn.