Purple Ghost

It’s a full house on a Thursday at KADIST Paris, which is hosting a discussion between Amal Khalaf and Farah Al Qasimi, preceded by a screening of the latter’s film Um Al Dhabaab (Mother of Fog).

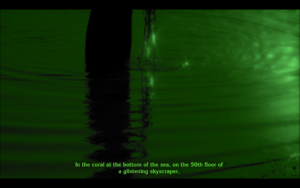

Green and purple are everywhere in Farah’s film. Like the night vision binoculars, a ‘passive’ military technology. Voyeur-chasseur. The vision impeded by night is also impeded by fog: the fog of the sea and the fog of the dust in the sand on the roads. As in every Pirates of the Caribbean film, the one who cuts through the mystery and the fog, the phantom ship, makes light of the passage of time, which falls on the waters and the bones.

Pirates threaten established systems, they play with codes – watery hackers. Dead or alive, they haunt marine discourse. Jinn of the seven seas. Farah Al Qasimi offers us the gulf by sea.

Um Al Dhabaab (Mother of Fog) proposes to make ghosts speak through different incarnations. An entertainer dressed as Jack Sparrow anchors a dummy Black Pearl. This captain, an immigrant to Dubai, has seen it all, from Iraq to Somalia and Iran. ‘The sea is very rough sometimes’. There are no masks on this floating stage, just a line of kohl and a few plaits. Whose story is this individual telling when he performs for tourists?

Al Qasimi will show us throughout his film: ghosts don’t just appear at night, they are with us all day too. The past comes back when the sand is stirred up and the powder of the remains is lifted. This film is a bit like a necessary excavation for the commemoration and preservation of rejected memories.

First hunted down by the Royal Navy during British colonisation, the pirates of the Gulf were then erased from memory by the capitalism of the UAE. To become an ideal trading partner and overturn the racist stereotypes of their supposed barbarism, Emirati society rejects one culture and exposes another. These imperialist overtones still infiltrate myths and customs.

In the conversation that followed the screening, Farah Al Qasimi set out her analysis of a twofold movement underway, of erasure and recovery, to manipulate the notion of truth. This is what she intends to illustrate in the film, throughout this ghost hunt, this ‘State fantasy’ as she explains it: leaving certain practices behind in order to exist in the world according to a bankable national narrative.

On the one hand, there is the cultural erasure of a spirit of resistance, of left-wing Emirati rebels in the 1970s, of Communist ties in the early days of the Ba’ath party, and on the other, a kind of colonisation under way in the United Arab Emirates, the omnipresence of British soft power in schools, radio stations, eating habits and so on.

From this observation, she begins to question the notion of truth. Fiction or not, there is an intrinsic freedom in oral histories, a floating zone that does not need to be determined. This ambiguity can also be found in her photography, where she creates images that question the presence of memory in space. Her images, both moving and still, are invitations to question our family and national narratives.

Opposite Abu Dhabi, nearly 2000 km to the west, in another country, is the setting for the film Love & Revenge – غرام وانتقام, directed in 2021 by Anhar Salem.

Although Love & Revenge – غرام وانتقام tells of the emotional alienation we have developed in the face of digital interactions, the persistence of social control, everywhere, and its destructive power, I also saw in this film the freedom of a generation that overflows, sacrifices, reverses and breaks.

Geographically distant, this film nonetheless reflects the same desire of a young woman artist, living in territories that have long been silenced and/or ignored, to tell the story of their reality and to question the mechanisms of domination and violence at work in the spaces they occupy today. Between intimate spaces and suburban exteriors, the female characters also re-enchant their daily lives through fiction.

نرجسية بحتة، بتّ أرى الجمال في الخطيئة… بتّ أرى الجمال الكامن في الخطيئة، الجمال المبعثر، المزدهر، متزعزع في كل مكان. يداهمك للحظات يشعرك فيها بالإيمان والحياة، ثم يفر سريعًا لحياةٍ وخطيئةٍ أخرى

Absolute narcissism; I’ve begun to see the beauty in sinfulness. The hidden beauty of sins, the scattered beauty, the blooming beauty; all around me. It breaks into your heart, and revives you, and then it passes from your sight into another life, and another sin.

-The Book of Sens, Doody

Whereas Farah Al Qasimi’s film criticises imperialism and colonialism, Anhar Salem’s film is more concerned with social control and patriarchy. The artist reflects on the question of adolescence and the need to go against the established rules in order to build oneself up and grasp the environment in which to grow and evolve. In an environment as tightly controlled as Saudi Arabia, how can you be a rebel?

During an interview, she gives me Pascal Menoret’s book, ‘Joyriding in Riyadh: Oil, Urbanism, and Road Revolt’, published in 2014, as an illustration of this rebellion. Speed and putting oneself at risk in potentially lethal acrobatics become the nerve of the rebel experience. Mostly male.

Anhar Salem calls them ‘crazy’, these young people who push the limits every day, and bend the rules a little more. For the production of the film Love & Revenge – غرام وانتقام, filming took place remotely, with her sister (Ansam Salem), who practises photography, playing her own role and that of cinematographer on location.

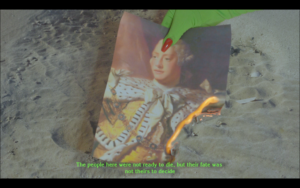

To produce the images, her sister, her niece Doody – the main actress – and all those who took part put themselves in danger, for example by filming in public places without permission. Producing this film was a committed, militant, family performance: her other sisters and her mother also appear in the film. A women’s story.

In a text written for the Cinémathèque Française, the artist writes: ‘The film is an attempt at catharsis for us and for them at that time, I couldn’t say exactly what was going on, we were afraid, so we decided to write this cyber-fairy tale’.

Anhar Salem includes a number of quotes in the film. Inspired by ‘Throw Away Your Books, Rally in the Streets’, by Shūji Terayama, broadcast in 1971 a new-wave portrait of student youth between rebellion and disillusionment, which the artist associates with this feeling of straitjacket of Saudi youth. She adapted an extract from it: for Doody ‘Japan is so boring no one wants to dance’ becomes ‘The World is so boring nobody wants to dance’.

Anhar Salem’s work is set in a contemporary context: after the oil boom, the sudden and exponential advent of a new modernity has overturned the paradigms of her country and her native region. It’s not just a question of capitalism and individualism, but of a rentier state, where everything comes from public money, and where the king is nicknamed ‘baba’. Daddy’s money.

In an area where consumerism is linked to the experience of sudden and exacerbated opulence, influenced by Western culture, new frames of reference come into conflict with a pre-existing system of moral values. Faced with this upheaval, society needed to be restructured, and the powers that be wondered how such a shift could be contained.

With the advent of the internet, which has enabled content to be disseminated more quickly and more widely, the distinction between the private and the public is breaking down, creating a new dilemma in society. The advent of images, particularly animated ones, which until then had been virtually absent, was unleashed by television, then computers and mobile devices. The artist explains how, in order to compete with the images produced by individuals, fields such as advertising have had to reinvent hitherto invisible figures, such as the Saudi woman, and integrate an imaginary of the private into the public domain, in order to control its representations. It is this phenomenon that Anhar explores in his 2021 found footage film ‘Tag Me if You Can’.

Faced with censorship, imagination and fiction become the tools of the young and the marginalised. Nevertheless, in Jeddah, it is impossible to ignore everyday reality, and its contrast with the new utopias.

This is precisely why Anhar uses the camera on his iPhone to make his productions. In front of the lens of a mobile phone, the protagonists behave differently than they would in a studio shoot. The awareness of being filmed by an everyday tool – which the actors themselves have mastered – has an impact on the way they portray themselves, with the film escaping the classic or authoritarian atmosphere of a shoot, conferred by the traditional camera.

For the new generation, the teenage crisis is taking place via the internet, and social networks in particular. Anhar remembers the moment she had access to the internet and that ‘overwhelming’ feeling. However, she adds, ‘The reality did not change: It was not freedom as I thought’.

Some inroads have been made. Before 2015, Twitter was a platform for Saudi feminist movements, a means of protest. But in 2015, the blue bird has become a bird of prey that threatens and condemns. To prevent dissent, the government is setting up a whistleblower application, whose name in Arabic could be translated as ‘We are all security’. Users can denounce physical and digital activities that contravene the law by reporting them via the platform. This information is then used to initiate legal proceedings. In these trials, it is the pseudonyms that are accused, but the penalties are very real.

When a new generation is born with the Internet, they don’t understand the threat that platforms for sharing images and words can represent. In the film, the night, the music, the colours and the notifications are all hypnotic and oppressive stimuli that convey the feeling of claustrophobia that grips Doody. The main character suffocates like a panic attack, provoked by the gradual loss of control over her Instagram ‘she’.

This story, which was supposed to end at the end of the film, continues with a cruel aftermath in reality. Doody died in March 2022. In the text dated the same month, for the Cinémathèque française, Anhar Salem says: ‘Doody’s suffering was enormous, and the film was too small to contain it’.

Doody, whose real name was Badriah Aljaidi, was a poet and writer. At the age of 13, she wrote under her birth name and won a writing prize for teenagers. The competition asked participants to interpret different subjects. Doody told the Saudi newspaper ‘Sabq’ that she won the competition after entering three short stories about self-confidence, kindness and progress.

Writing has never left her. Excerpts from her collection ‘The Book of Sens’ punctuate the film: these words recount Doody’s feelings at the time of the contempt trial. She wanted to embody the body and soul of a diva, so she wore blonde hair, like Madonna of Jeddah, and a tattoo of Cleopatra on her plexus, like Rihanna.

This transformation into a diva was accompanied by a new visual production: Doody started taking photos, and Lulu (Lujain), her sister, accompanied her. One day, outside the mosque, her boyfriend prostrated himself before her, a blonde, modern-day goddess. Doody’s sister Lulu was sentenced to three years’ imprisonment, for taking a photo of this blasphemous scene and helping to circulate it on the Internet.

Anhar pays particular attention to young people who are growing up with the possibility of inventing themselves on Instagram, but society’s ban on self-fulfilment. Reading the work of philosopher Hans-Georg Moeller, on the construction of personal identities throughout history, enables her to put words to this phenomenon, which she has been observing for some time.

Moeller chronologically presents three typologies of self-construction. ‘Sincerity”: conforming to a shared model, then “Authenticity”: moving away from the model towards individuality; then, in the contemporary era, “Profilicity”: born of the crossroads between the Internet and liberal capitalism, this is the process of constructing a profile and then striving to become it. He will write a text for Anhar about the poem declaimed by Doody at the end of Love & Revenge – غرام وانتقام. It is this latter typology that Anhar Salem sees emerging around her among her relatives in Jeddah.

Among all the artist’s phrases that I jotted down on my phone during our meetings, one title: ‘Social media as fiction’. Anhar Salem’s work focuses on the desires that drive us to consume and exist on social networks. It is a collective hypocrisy that sustains this scopic power, since the content consumed is born of individual narcissism, discredited or even punished by the law or morality, outside the digital screen. This is our new, unacknowledged addiction to high-performance self-indulgence.