لِبيروت (To Beirut)

For the original German version of this text please visit pokusberlin.com

I often wake up with an earworm that I can’t really explain. A song plays incessantly in my head and since any fight against it would be futile, I have to get along by playing the song, more than just once, and singing along very loudly. And so on this Sunday morning, funny coincidence or secret oracle, Fairuz’s voice resounds in my head. لِبيروت (To Beirut). At this point, I don’t know what I’m going to do in the afternoon. I turn on my loudspeaker and sing along. As usual, the catharsis works: the song fades a little so that my other thoughts get more space again. Fairuz’s voice is now a gentle and pleasant presence; it will accompany me all day.

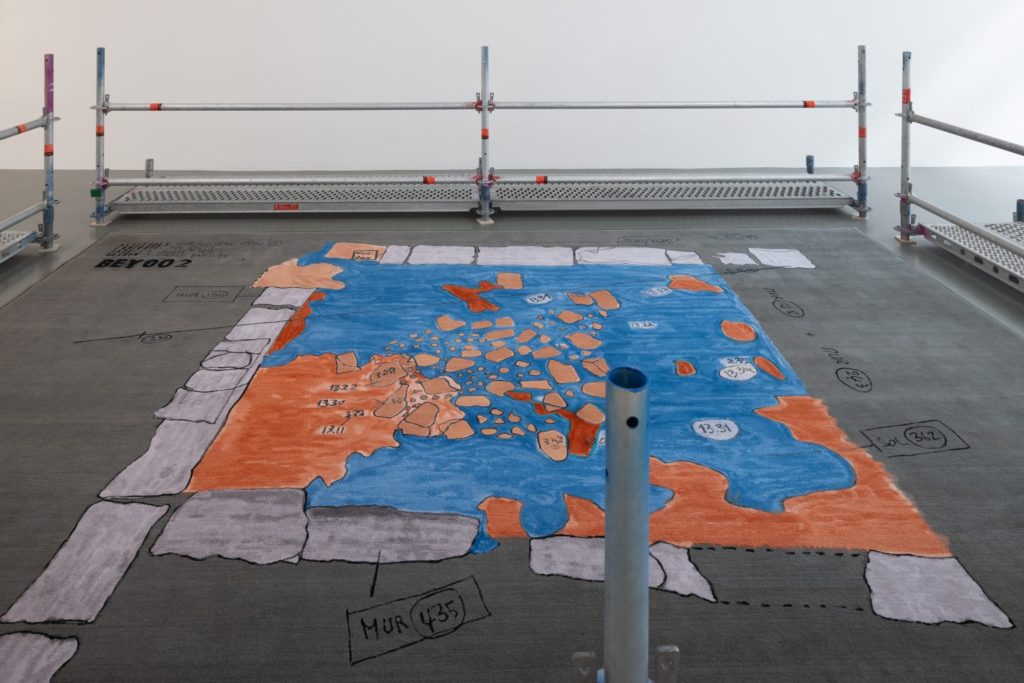

Late in the afternoon, I spontaneously decide to visit the daadgalerie in the Oranienstraße. Currently on view is a solo exhibition by the artist Paola Yacoub, entitled „BEY002“. Her central work thrones in the middle of the exhibition space: a very large, mighty carpet (4.82 x 3.54 m). I look at it for a while and then make a tour to take a look at the other exhibits. My intuition tells me that I will only really understand the meaning and importance of the carpet when I have seen the rest of the show.

On a wall facing the carpet hang two rows of newspapers that have been selected by Paola Yacoub. They are issues of L’Orient-Le Jour, a weekly Lebanese magazine in French. The focus is mainly on the satirical comics „The Art of Boo“, whose author, Bernard Hage, lives in Berlin, as does Paola Yacoub. These are issues of the newspaper published shortly before and after 4 August 2020 – the day of the explosion in the port of Beirut. The drawings caricature the political situation in Lebanon. The comics were not cut out or otherwise isolated by Paola Yacoub: with each newspaper page, various other contents are also exhibited. They form small random excerpts of current affairs and everyday life in Lebanon to skim over: a report on the success of a young singer, a cake recipe… all viewers can choose from these side articles what appeals to them. One of these articles, a text by the journalist Gilles Khoury, arouses my interest: I read it with more attention and really like it. It is a – fictional? – narrative describing the complex relationship between a man and Lebanon, his homeland. Complex in the sense that the political situation in his country makes him desperate but that he cannot decide to go into exile, even when he is mentally just about to set sail. This article, as well as the others I haven’t read so thoroughly, is sort of coincidentally included because it was printed on the same page as „The Art of Boo“. I like its ambivalent and ambiguous position: basically, it doesn’t belong to the exhibition, yet it is available and fits in a way to the show. The drawings by Bernard Hage and the narration by Gilles Khoury touch me. They settle in my mind, where they find a place next to Fairuz, and accompany me through the rest of the exhibition.

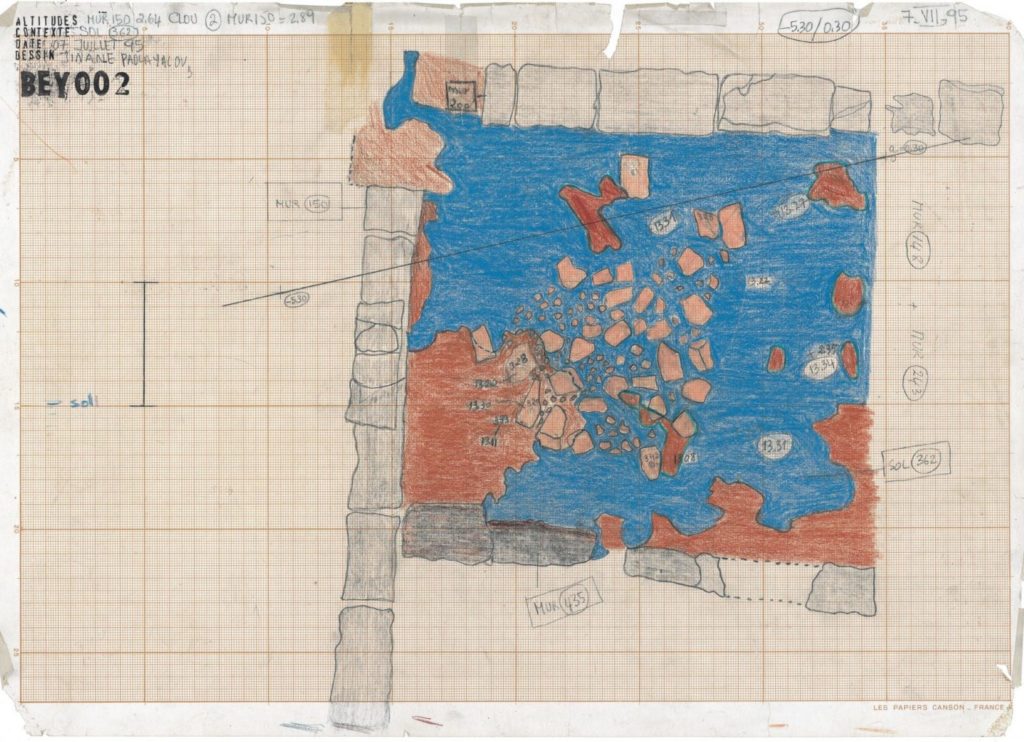

Next I turn to an area of Paola Yacoub’s drawings, which are more precisely archaeological protocols. When Beirut was to be reconstructed after the civil war (1975 – 1990), excavations were carried out in which Paola Yacoub also participated1. During the war, the city centre was massively damaged and destroyed by bombing. The remaining buildings were to be demolished in preparation for the planned reconstruction. Areas were thus defined throughout the city where different teams of archaeologists were to work at emergency excavations. The artist Paola Yacoub had already left her hometown Beirut for a few years when she returned in 1993 to work on the excavation of the site “BEY002”. As described by curator Corinne Diserens in her text, “Six eras were superimposed on its ground: Ottoman, Byzantine, Roman Republic, Roman Empire, Hellenistic and Persian. Yacoub was responsible for recording the different strata as they gradually emerged. To facilitate the reading of her drawings, she created a completely new graphic code, assigning a different colour to each stratum discovered.”2The spectators are thus confronted with numerous archaeological protocols: scientific records of the ongoing excavations in the „BEY002“ district. Schematic representations, colour coding and written notes with numerous abbreviations that are quite mysterious for an outsider.

One of these archaeological drawings from 1995 has been woven in the carpet, which is not far away in the same room. The piece was made in 2012 by the renowned Manufacture des Gobelins in Paris. About twenty years after the first emergency excavations in BEY002, a dialogue was established between Paola Yacoub and the Parisian Manufacture. The carpet took about four and a half years to make. The work has a warm, both splendid and calming aura. In many cultures, especially in Arab countries, the carpet is a valuable object, coming from ancient traditions, which are associated with a complex craft. The Parisian Manufacture des Gobelins is worldwide renowned for its expertise since the 15th century. However, most techniques were brought to France through exchanges between the Ottoman Empire and Europe. Tapestries can hang on the wall or lie on the floor. They are jewels for the home, secretly absorbing the footsteps, the tears and joys, cries and whispers of entire families. A precious rug is often passed down from generation to generation. A carpet can also be a place of prayer or meditation and thus have a devotional value. Thus Paola Yacoub uses this almost sacred object, which can be a symbol of home, as a surface to carry an archaeological drawing. This transfer first establishes an analogy between the archaeological practice and the carpet as a woven fabric: both practices consist in bringing to light superimposed layers – respectively of ruins and of thread. Mysterious networks of stone or of wool spin invisibly beneath our feet and anchor us. They secretly connect us to an older history of which we are not actively aware, yet which strongly influences our behaviour, culture and identity. In this analogy, the carpet and archaeological practice embody our relationship to the ground and to our history. They serve as a silent mediation between several generations.

Nevertheless, the carpet also stands in a contradiction to the representation it carries. For it is a symbol of home, while the drawing is a representation of the many homes that no longer exist. The drawing brutally points to the reason why this carpet cannot fulfil its role as a carpet. Even in the exhibition space, where it lies magnificently on the floor, it cannot be walked on. Its original function and thus its essence are taken from it. There were no longer any dwellings in the grounds of BEY002. The archaeological excavations were imposed by the civil war: they had to be completed before the reconstruction that was necessary after the war. But they could not have taken place without these destructions. No buildings may stand on grounds that are to be excavated by archeologues. Destruction is a prerequisite of archaeology when it comes to researching the past of an inhabited place.

Demolition and new construction are also part of the contemporary history of the German capital and strongly shape its identity. Despite this, Berlin’s ancient history is very poorly known and the knowledge we have is fragmentary, compared to other European cities. The major excavations and archaeological research have only been undertaken in recent years3. Berlin, like Beirut, is a city in quest of its history and to some extent in search of its identity. The ancient times are not well known and the history of the last century is particularly painful. Berlin is a city whose present is built on a fragile past.

The various elements of the exhibition compose a peculiar portrait of Beirut. Like on a negative film, the complex identity of the city is presented through what no longer exists. What matters the most, in this introduction to Beirut, is what has been destroyed by the war, by the explosion in the port, and during earlier eras. We get to know Beirut through what has disappeared or been buried. Paola Yacoub explains that she has rediscovered her own city because the archaeological excavations made her perceive it differently. „I had the rare privilege of excavating in the city of my childhood, and not in a faraway country as it is often the case. I was able to see the city of Beirut from below, from the depths of its history. It was a shock. I also discovered that this history was still to be constructed, and that certain urbanistic conjectures were false. My knowledge of the city was turned on its head. But since then, the grounds are an obsession of mine.”4

“The Art of Boo” comics, the protocol drawings and, of course, the tapestry all point to scars; to events that have left injuries more than imprints on Beirut’s body. Fairuz’s song also speaks of a wounded Beirut, of ashes and blood, of darkness and despair5. Nevertheless, like Paola Yacoub’s works and like Gilles Khoury’s text, it is also a declaration of love that expresses nostalgia and deep attachment at the same time.

I cannot help but think that this exhibition is not taking place in Berlin by coincidence. Berlin, as the city hosting the show, is never mentioned in the exhibition, nor is a parallel between Berlin and Beirut to be read anywhere. Nevertheless, it seems to me that Berlin is secretly portrayed as well, together with Beirut. Perhaps through similarities that I cannot disregard. Berlin, who like Beirut, is still branded by numerous bomb attacks. Berlin, whose wall fell barely a year before Beirut’s green line. Berlin, whose war wounds are still freshly healed and whose history has been scientifically researched in a very recent time.

I see two cities in quest of their own past; I see an arduous attempt at self-discovery and a present identity marked by trauma and uncertainty. This is how I experience Berlin and this is how Beirut is portrayed by Paola Yacoub. I don’t want to draw a linear analogy between two wars and following traumas that are most certainly not comparable. Berlin is at a different stage of its reconstruction and I know how privileged its population is. Nevertheless, the exhibition strikes me as evoking a secret bond of solidarity between Beirut and Berlin. As if Paola Yacoub had skilfully crafted a second, invisible tapestry by weaving the identities of her two cities together. Perhaps also in a gesture of hope.

من قلبي سلامٌ لبيروت

و قُبلٌ للبحر و البيوت

From my heart, a salute to Beirut

An embrace to the flowers and to the houses

1 Detailed information on the excavations is available in the booklet of the exhibition. Here is a digital version of the publication.

2 Corinne Diserens, „Memory needs the ground“, in the booklet of the exhibition Paola Yacoub. BEY002, Daadgalerie, Berlin, 2021, p. 39 – 40.

3 Further information (in German) on the excavation in Berlin Mitte, which took place from 2008 to 2015 under the direction of Michael Malliaris: “Berlin fast vergessene Mitte”, Hakan Baykal, Spektrum, 25.05.2021: https://www.spektrum.de/news/ausgrabungen-berlins-fast-vergessene-mitte/1867114Further information on the excavation in Berlin Biesdorf (1999 – 2014) on the website of the Neues Museum: https://www.smb.museum/ausstellungen/detail/berlins-groesste-grabung/

4 “Interview with Paola Yacoub, March 2021”, Corinne Diserens , in the booklet of the exhibition Paola Yacoub. BEY002, Daadgalerie, Berlin, 2021, p. 55.

5 Also Paola Yacoub writes that “transposing this document onto a carpet indeed seems like a desperate gesture” Cf. Paola Yacoub, “BEY 002, This is not a fiction, 2021”, in the booklet of the exhibition Paola Yacoub. BEY002, Daadgalerie, Berlin, 2021, p. 6.

daadgalerie

Oranienstraße 161

10969 Berlin

https://www.berliner-kuenstlerprogramm.de/en/